CAPA has reported extensively on the proliferation in airport P3 projects that took place between 2017 and 2020 in particular, with public and private sectors joining forces to build new and much needed infrastructure, from terminals to car rental centres to people movers, much of which is coming into use now, to replace crumbling antecedents.

But the 26-year-old airport privatisation programme that was intended to lease a variety of airport types, from reliever to principal hub, remains stuck in limbo, with only one success to its credit.

The tenet of this report is events at Austin, Texas.

There, the city council is trying to acquire a privately run terminal that is attractive to ULCCs, and for a pittance, so that it can extend the terminal it operates itself. This in the wake of the collapse of the lease procedure for St Louis Lambert Airport, which had attracted worldwide interest, and it does no favours whatsoever to the airport privatisation impetus.

Summary

On 16-Jun-2022 Austin City Council, in the Texas state capital, voted to undergo 'Eminent Domain' proceedings to acquire the South Terminal at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport (ABIA) from the private operator LoneStar Airport Holdings, which has been operating it since Apr-2017.

At the same time, the council approved USD46 million in construction works associated with addition of gates to the airport's Barbara Jordan Terminal, and USD8 million for engineering services related to the airport expansion.

There is a considerable difference in size.

The Barbara Jordan Terminal handled over a million passengers a month in 2021, compared to approximately 25,000 at the South Terminal.

If successful, the City would then close the facility and relocate the tenants, the ULCCs Allegiant Air and Frontier Airlines, to facilitate advancement of the city aviation department's airport expansion and development programme (AEDP).

LoneStar, which took on a 40-year lease for the facility in 2016, said the operator is assessing its options, stating that the decision will lead to "expensive, time consuming litigation".

Not only that – it could further set back attempts to privatise the US airports business.

Efforts made since the Airport Privatisation Pilot Programme in 1996 (subsequently amended and improved as the Airport Investment Partnership Programme) had only actually privatised two commercial airports by lease, one of which was returned to the private sector seven years later, while the other is not even in the US proper.

Latterly there has been a surge of interest in public-private partnership (P3) transactions, as an alternative, to build or refurbish and operate individual terminals or other infrastructure at airports across the country, but that movement could be compromised if Austin City Council is successful in an attempt to close down a privately operated terminal within a handful of years of the commencement of a long term lease.

When it opened, as a P3 venture between the City and LoneStar Holdings, the South Terminal expanded the capacity of the airport with three new gates within a single story building in the southern part of the airport, with its own on-site parking, and marked the completion of a USD12 million renovation.

Subsequently it expanded to 10 gates.

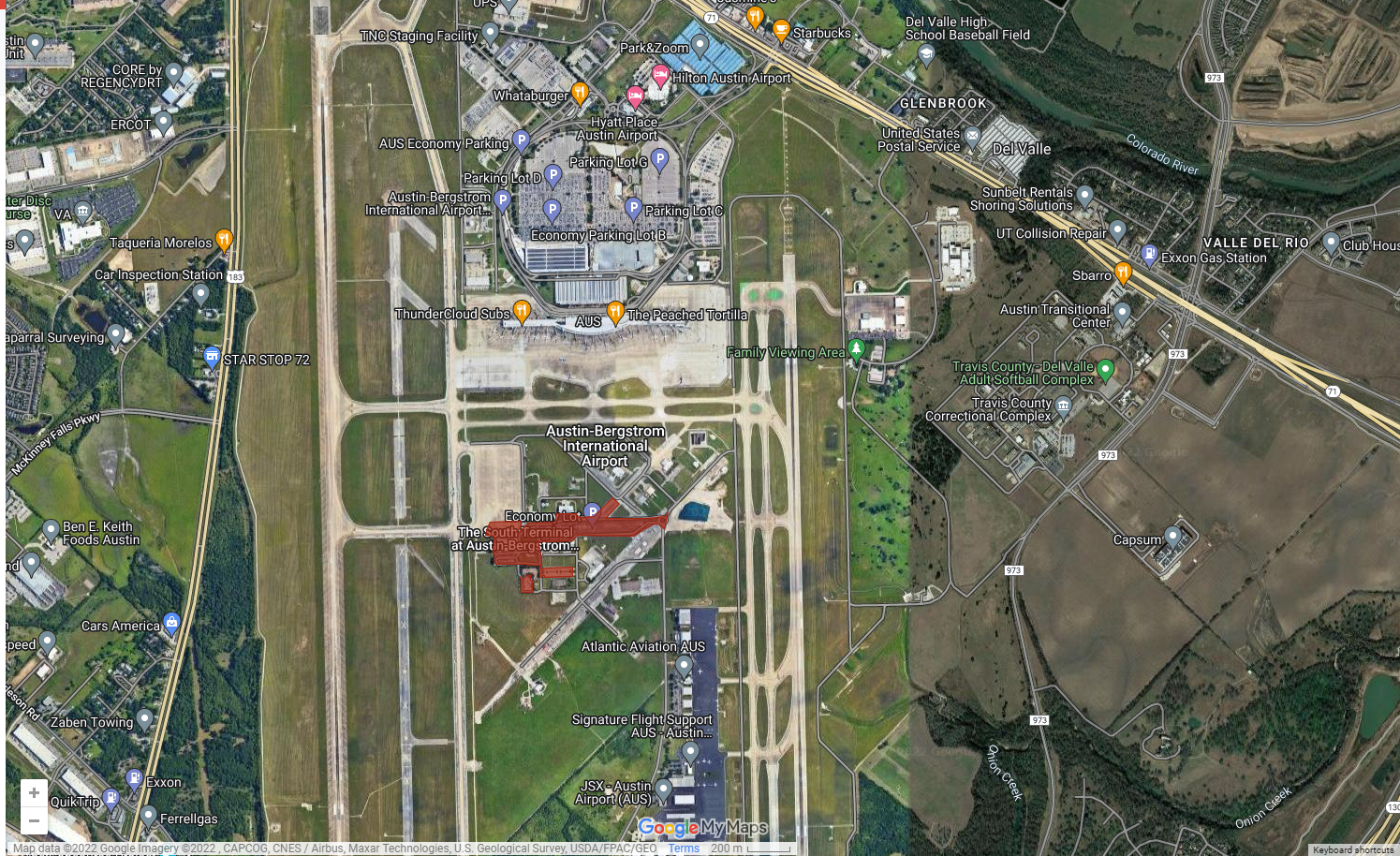

Location of the South Terminal (marked in red), Austin, US

Source: Google Maps.

The South Terminal was promoted at the time, rather hopefully, by its CEO Jeff Pearse (who remains in that position today) in this fashion: “Ground-level aircraft boarding invokes the golden age of mid-century air travel – when passengers walked across the tarmac to board their flights. That golden age became the basis for our interior design. Mid-century cues in furniture and finishes – utilising textures and colours native to the Texas Hill Country will provide Austin travellers an airport experience as unique as our city!”

At the same time, he committed the terminal to incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices and reporting.

It is not the first attempt to operate a terminal privately at ABIA.

Two decades ago another ‘low cost’ terminal was built there, that one financed by General Electric, and specifically to serve the declared needs of one airline, a Mexican one.

The H1N1 outbreak led to discontinuance of use of the terminal in 2009.

LoneStar Airport Holdings is a limited liability portfolio company set up in Delaware in Jan-2016 and employing funds managed by Oaktree Capital Management.

In 2014 L.P. Oaktree, the world’s largest distressed-debt investor, agreed to acquire the Highstar Capital team, an organisation which had been very active in airport M&A deals – for example, London City Airport, and the Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico (one of the two private lease-operated airports referred to above).

Highstar/Oaktree have also been active over the past decade in the bidding for leases at, inter alia, St Louis Lambert and Westchester (New York state) – both of which were terminated – and the Central Terminal Development at New York La Guardia Airport; and also in discussions with Nashville City Council over the potential privatisation of the airport there.

In Nov-2020 Royal Schiphol Group and Oaktree Capital Management entered an alliance to pursue airport investment and management opportunities in North America. The parties will focus on infrastructure investment and implementing operational and sustainability best practices.

But for all this interest, no new deals were agreed, and Oaktree has exited both the London City and Puerto Rico airports, leaving it with only the Austin terminal in its portfolio.

Oaktree’s deepest interest appears to be in energy, and particularly shale gas, and in the transport sector, ports.

So how has this situation come about? It isn’t something that happened overnight.

In Aug-2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, it emerged that Oaktree was exploring the sale of a portion of the concession to other investors. Then, in the November of that year the City’s Department of Aviation expressed interest in regaining control of the South Terminal, subsequent to that revelation.

Further action was delayed by the pandemic until now, when the lawsuit was announced by the City, with the intention of further and long term expansion of the airport under the Aviation Department's Airport Expansion and Development Programme master plan to 2040 – given as the reason for wishing to remove the terminal, which it valued at USD1.95 million.

Earlier this year the City offered to buy the terminal at that price – a move deemed to be “offensive” by LoneStar Holdings, which added this week that it believed the City was acting “in bad faith” (previously the City had mentioned a figure of USD10 million).

By way of explanation, 'Eminent Domain' refers to the power of the government to take private property and convert it into public use. The Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution provides that the government may only exercise this power if they provide ‘just compensation’ to the property owners.

Its CEO has also said, "at a time when the airport needs more gates and terminal capacity than ever before, airport leadership believes the best course of action is to demolish the South Terminal and squeeze two more airlines, 25,000 more flights and more than a million additional passengers per year into the already overcrowded Barbara Jordan Terminal – all at a time when disruptive works to optimise the Barbara Jordan Terminal are underway."

The Aviation Department’s CEO, Jacqueline Yaft, has argued that Eminent Domain is “a necessary step for the airport's future that will improve operations”.

Her view is that "the relocation of the airlines operating at the South Terminal to the Barbara Jordan Terminal will not decrease the service and benefits that passengers have come to expect from AUS. Opportunities for relocating South Terminal tenants and their employees to the Barbara Jordan Terminal are also being explored. The Department of Aviation looks forward to working with each tenant on a customised transition plan. These changes will fulfil the goals of building a better AUS for the future while delivering and upgrading passenger experiences."

Essentially, what the City wants to do is to demolish the South Terminal as part of a USD4 billion expansion plan that includes building a new mid-field concourse with at least 10 gates in its place.

It was only in Apr-2022 that LoneStar had pitched its own proposal: to move the South Terminal further south and vacate the property the airport wants to be demolished.

Within two years, Mr Pearse claimed, the so-called ‘South Terminal 2.0' would add up to 10 gates (the same as the City’s plan for the midfield terminal of its own), up to five security lanes, 22 check-in counters, and more than 154,000 square feet of terminal space.

The scheme would cost USD140 million, versus the City’s USD4 billion for much the same result.

An illustration of the proposed ‘South Terminal 2.0’ at ground level

Source: LoneStar Airport Holdings.

As always, there is at least an element of politics involved in disagreements such as this.

Three years ago the proposed lease on St Louis Lambert International Airport, which had attracted worldwide interest from serious investors, and which was well on its way to a deal, was scuppered by the city’s mayor.

In this instance, LoneStar claims that the South Terminal 2.0 plan was developed at the request of city officials in 2018, when the airport was run by a long-time director, Jim Smith, who then retired in 2019.

Shortly after Ms Yaft took over it is claimed that the City abruptly ended conversations with LoneStar about creating a new South Terminal. She is said locally to be the individual who proposed offering LoneStar USD10 million for its terminal.

Ms Yaft’s LinkedIn profile reveals that she has worked in senior executive positions for Denver International Airport and Los Angeles World Airports, as well as being President of Aviation Management Solutions LLC before joining ABIA – “a women minority owned firm that specialises in airport and airlines operations, critical systems, emergency preparedness, and customer service”.

There is nothing there to suggest any politically inspired motivation for wishing to remove the terminal.

It may be of some consequence, though, that Austin City Council, while officially bipartisan, has all but one of its current council members, and the mayor, affiliated with the Democratic Party.

Since the Presidential election of 2020 there has been precious little support from the Biden administration for private sector participation in airport development. The 2018 Airport Investment Partnership Programme (an initiative of the previous administration) has created no new deals for airport leases (one is pending and has been since 2010) and comparatively few new P3s for specific infrastructure as a result of this limbo (almost all the existing ones were agreed before Nov-2020).

So there is little to be optimistic about the private sector riding to the rescue of US airports when they most need it to start with, and it could be argued that forcibly excluding such a private sector firm from running a terminal just a few years into its concession contract, and for derisory compensation, might well drive the final nail into the coffin of the programme.

What board of directors in their right mind would sanction such an investment?

Moreover, for the two operators at the South Terminal, Allegiant and Frontier, it would mean mixing their business model into the one employed at the Barbara Jordan Terminal.

That should not be an impossible task, the ratio of low cost capacity to full service at ABIA is 46.8%:53.2% (week commencing 20-Jun-2022). Those two ULCCs account for a small part of that low cost capacity, and there are other LCCs (Southwest, with almost 40% of capacity) and ULCCs (Spirit, which Frontier is trying to acquire). They would hardly be alone.

On the other hand, it would send out a message that the ULCC brand is not considered to have high importance at ABIA, and that could have a knock-on effect with other airports’ appreciation of that business model.

This is not the first time a groundbreaking budget terminal has bitten the dust, if that is ultimately what happens at Austin.

Both of the low cost terminals at Singapore and Kuala Lumpur which opened in 2006 in competition with each other have long since closed.

In Singapore its ‘Budget Terminal’ (that was its name) was razed and the LCCs reaccommodated in new, swisher terminals. At Kuala Lumpur the original low cost terminal, which was 20 miles by car from the main terminal owing to a convoluted road network, was also demolished, replaced by a ‘Taj Mahal’ of a much larger building, ‘KLIA2’, which in turn was supposed to be another budget facility but which actually catered for all airline models – and lavishly.

Different results, but at least the Singapore and Kuala Lumpur airports were driven by a schema. At some US airports it is sometimes difficult to appreciate what it is, and it can change very quickly.

As in so many aspects of life there, decisions seem at the very least to be influenced by a perverse political narrative, and right now it is hard to argue that privately operated airport terminals hold any sort of positive resonance in that narrative.